Results from 421 to 480 of 1081

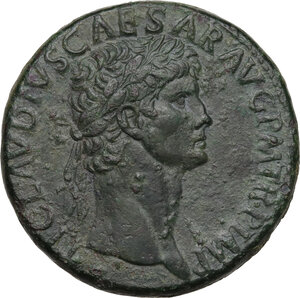

Outstanding Roma Sestertius

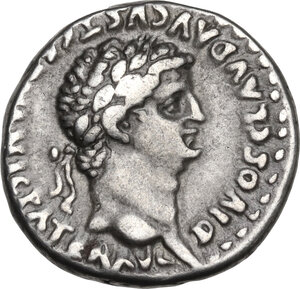

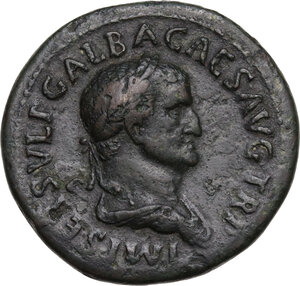

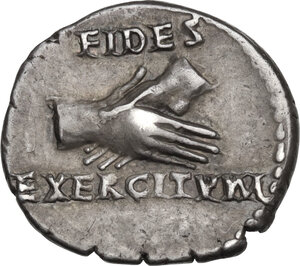

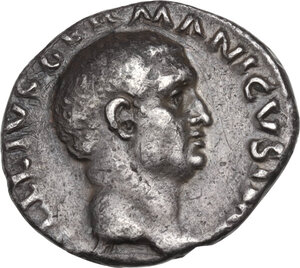

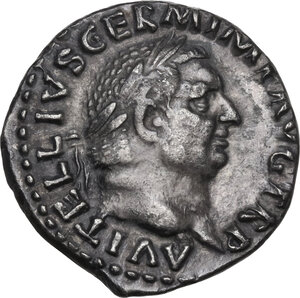

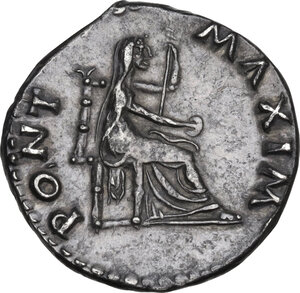

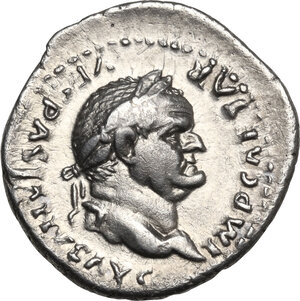

Impressive Vitellius' Portrait

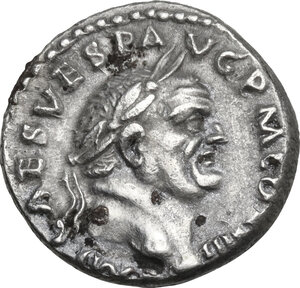

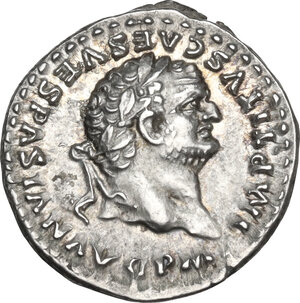

Spectacular Nerva Portrait.

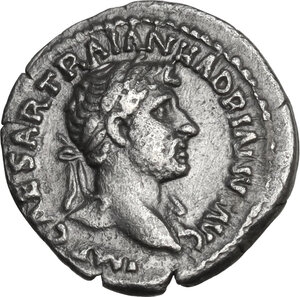

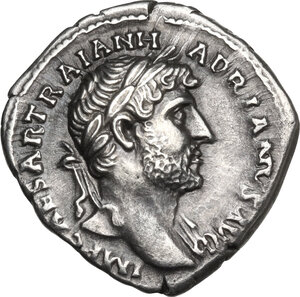

Outstanding Mustachioed Hadrian

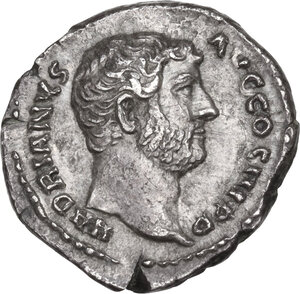

Impressive Hadrian Portrait

Enchanting Sabina

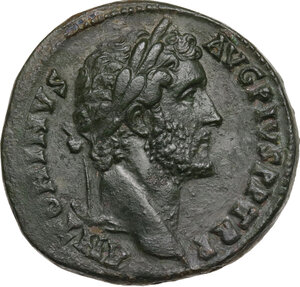

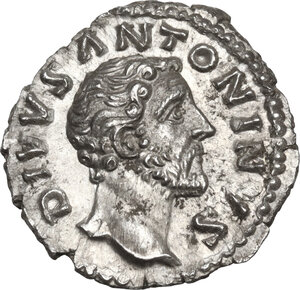

Exceptional Marcus Aurelius Sestertius

Spectacular Lucius Verus

Accurate Depiction of a Victimarius Scene

Impressive Caracalla's Sestertius

Lovely portrait of Plautilla

Results from 421 to 480 of 1081